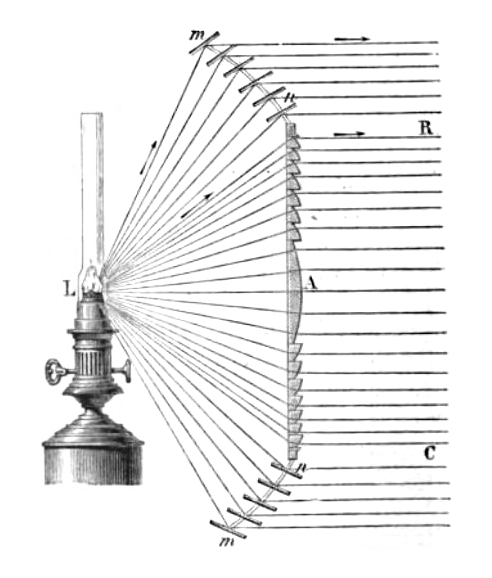

The lighthouse tower is, of course, the reason why the light station exists, and the tower is considered to be one of our most important artifacts. It was activated on November 1, 1887, with a first order fixed (non-rotating, non-flashing) Fresnel lens as its optic. Inside this huge collection of prisms and lenses sat a kerosene lantern with five concentric wicks. The Fresnel lens worked to collect most of the light rays emitted by the kerosene lantern and bend them so that they formed a single strong beam of light that could be seen nearly 18-20 miles out to sea.

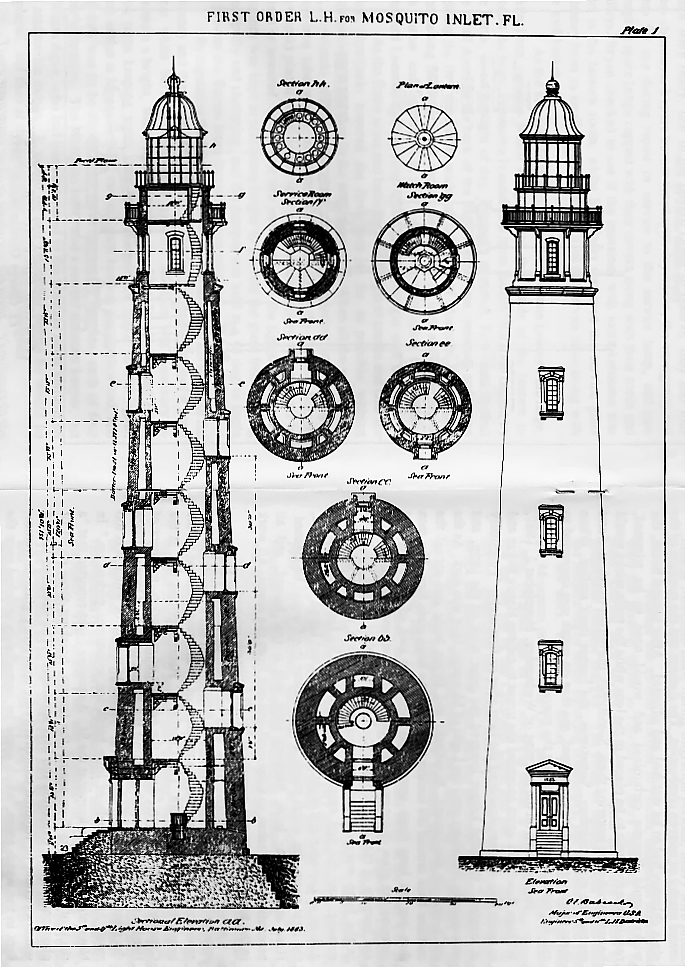

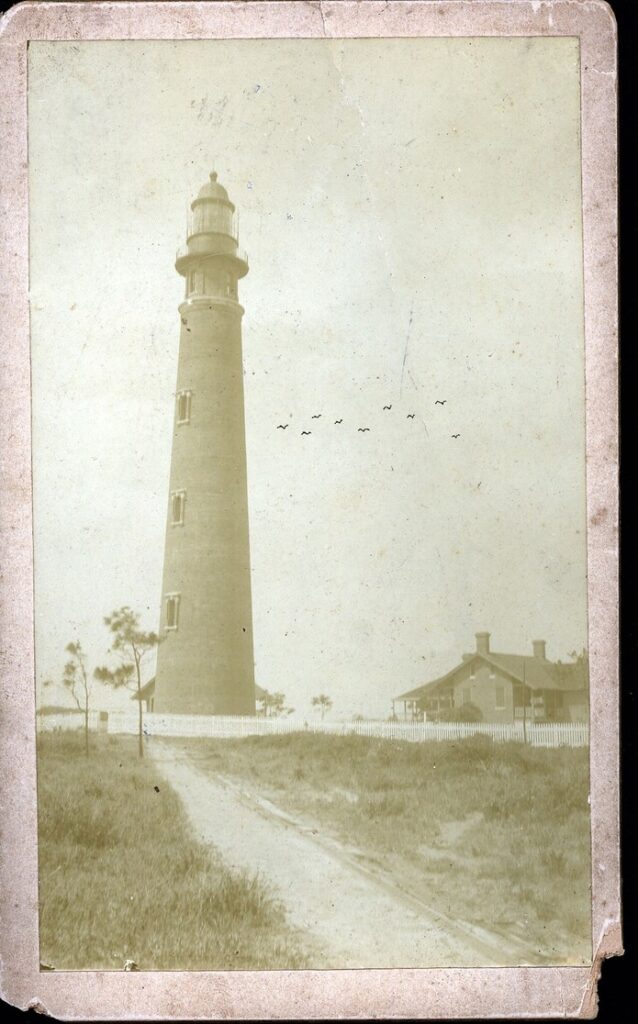

Plans for the Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse.

The tower was illuminated by a kerosene lantern inside a first order fixed Fresnel lens.

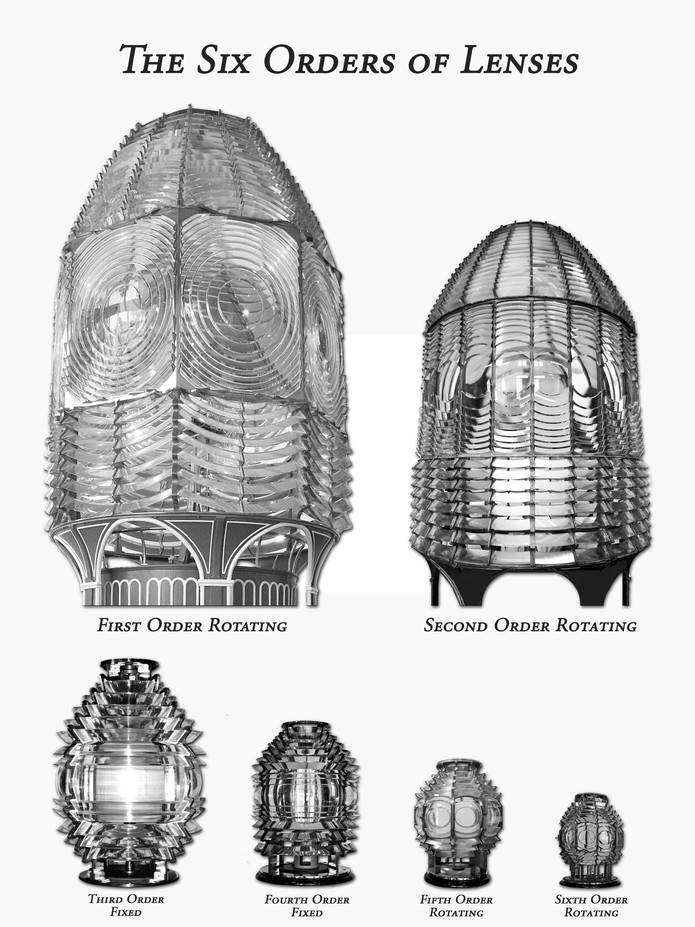

Order is the term given to describe the size of both fixed and rotating lighthouse optics. Traditionally, they range from sixth order (the smallest) to first order (initially the largest). As these lenses evolved, smaller sizes were developed and two larger sizes were created – the hyper radial and the meso radial. Very few of these giant lenses were produced, but, as the tower at Mosquito (Ponce) Inlet was being constructed, the initial plan was to place one in the new tower. Unfortunately, the lantern room was really too small to accommodate the extra large lens, and that lens was sent instead to Makapu’u Point in Hawaii.

The fixed first order Fresnel lens that originally illuminated the lighthouse.

In 1933, the Lighthouse Service decided to replace the fixed light at Ponce Inlet with a rotating, flashing optic powered and illuminated by electricity. So much population growth had taken place near Ponce Inlet that the fixed light was becoming hard to pick out from other lights in the area. The new flashing light was a third order that had recently been removed from a lighthouse at Sapelo Island, Georgia. The first order lens was dismantled, packed and shipped to the Lighthouse Service depot at Staten Island, New York, and its whereabouts after that remained undiscovered for many years. The third order’s characteristic or identifying flash pattern was six half-second flashes followed by an eclipse or period of darkness. The first five flashes were each followed by a two-second eclipse. The sixth flash was followed by a 17-second eclipse, resulting in a full rotation in 30 seconds.

This third order rotating Fresnel lens was first installed in the tower in 1933.

When the Coast Guard discontinued the tower in 1970, the third order lens was removed from the tower and shipped to the Coast Guard Museum for display. In 1973, as a result of requests by the Ponce de Leon Inlet Lighthouse Preservation Association, the third order lens was returned to Ponce Inlet for restoration and display. In 1982, the Coast Guard reactivated the beacon in the Ponce Inlet Lighthouse using a series of modern lighthouse optics. Following further restoration work, the third order lens was returned to service in the tower in 2004, and the Coast Guard granted permission for the beacon to become a private aid to navigation, maintained by the museum staff. The Ponce Inlet tower is still a working lighthouse today and uses the historic 30-second rotation and characteristic. The 175-foot tower is open for climbing, and yes, you are invited to climb the 203 steps up to the main balcony! But there are a few things to notice before you get there.

Our lighthouse is called a brick giant for good reason. Brick giant lighthouses are among the tallest in the nation, and the Ponce Inlet Lighthouse is the tallest in Florida and the seventh tallest in the US. The tower’s daymark or identifying color pattern is a brick red color called Venetian Red. This is not paint but rather a special mineral-based coating. The identifying color and pattern system for lighthouses was implemented by the Light-House Establishment in 1852.

As you enter the tower’s double front doors, you can see the amazing thickness of the brick walls. Here they are about eight feet thick, but as you climb the walls get thinner until at the top they are two feet thick. The tower is, in fact, a cone, but the interior is a cylinder which is 12 feet in diameter. The design for the lighthouse was taken from a standard brick giant plan drawn by Paul Pelz, a Light-House Establishment draftsman. Various modifications to the plan were made by the engineers who oversaw the tower’s construction, since changes in standard plans were typically made to suit local conditions.

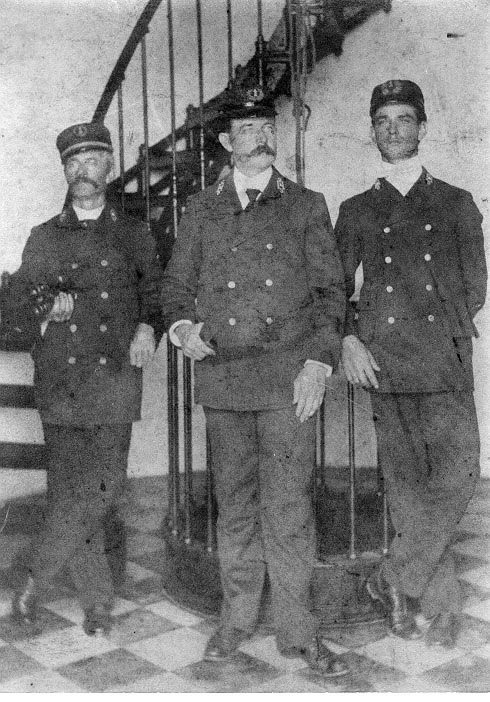

Principal Keeper Thomas O’Hagan and his assistants pose inside the tower entrance in this 1902-03 photo.

Although restoration work has been done over the years, the lighthouse tower is totally authentic, including the optic at the top of the tower – the same rotating and flashing third order lens that was installed here in 1933. In the entryway, you can see the original marble tile floor and the original iron staircase, manufactured by Phoenix Iron of Philadelphia especially for the Mosquito (Ponce) Inlet Light Station. Near the main balcony, a support beam with the Phoenix name embossed is visible.

The Phoenix Iron Company’s maker’s mark can be seen on a beam near the top of the stairway.

The entrance also features a mystery structure which is known as a weight well. It was part of the standard tower plan and had a function which was actually never needed at Mosquito Inlet. Before lighthouses were electrified, rotating and flashing lenses were turned by means of a grandfather clock-style rotational mechanism that depended on heavy weights that were slowly lowered into the weight well as the beacon turned. Once they reached bottom, the lighthouse keepers had to crank them up to the top again to keep the rotation going. At this lighthouse, the original beacon was a fixed first order Fresnel lens which did not require rotation. In 1933, when the lighthouse tower was electrified, the rotating and flashing beacon was installed, but it was powered by a generator, not by a clock-work.

The weight well and the original marble floor and cast iron staircase.

As you start up the cast iron staircase, you may see a sign warning you about lightning storms. Even though the tower has a lightning protection system, we ask visitors to leave the tower while storms are in the area, just in case. After all, the tower can be an irresistible target for a lightning bolt!

Now imagine that you are a lighthouse keeper, carrying up a heavy five-gallon fuel can filled with enough kerosene to keep the beacon lit through the night. It’s a long climb up those steps, and on the way you may stop to read about Joseph B. Davis. Davis came to the lighthouse in 1918 as a first assistant keeper to Principal Keeper John Lindquist. He had served as Lindquist’s second assistant a few years earlier and received a promotion upon his return. On the night of October 26, 1919, Davis climbed the tower to light the kerosene lantern, but the light never came on. Second Assistant Benjamin Stone found Davis’ lifeless body in the tower where he had died of heart failure as he climbed.

There are lighthearted stories about the tower, too. One of the best was told by Helen O’Hagan Sintes, whose grandfather was Thomas O’Hagan, our second principal keeper, who served from 1893-1905. Keeper O’Hagan and his wife Julia had 11 children while they were here and child number 12 came along after the family was posted to another lighthouse. While serving at Mosquito Inlet, Thomas O’Hagan’s lively wife led a prank that has come down to us from her granddaughter Helen. After a long night of manning the beacon, the keepers had hours of work waiting for them to prepare the Fresnel lens for the coming night. The men would lower a bucket for the wives to fill with something good eat. One morning the women filled that bucket with dirty diapers, very likely in response to a comment by the men questioning what the women did with themselves all day.

Julia O’Hagan with one of her many children.

If you climb up to the main balcony, you’ll be treated with a spectacular view that, on a clear day, will enable you to glimpse Cape Canaveral’s vehicle assembly building to the south. The tower faces east, and the inlet, the ocean, Mosquito Lagoon, and the Halifax River can all be easily seen as you walk around the balcony. The tower was an ideal place to watch for enemy submarines during both world wars. Looking west you may spot the nearby Pacetti Hotel on the east bank of the Halifax River, and to the north lies the famous beach that was the birthplace of automobile and motorcycle racing.

Some historic photos of the lighthouse reveal a cage around the lantern room at the top. This cage was installed twice each year during migration season to prevent birds from crashing into the lantern room glass. Light from the beacon caused the birds to become disoriented and fly to the windows. Dozens of dead birds could be found at the foot of the tower each morning, and sometimes the impact from larger birds would actually break the glass.

A cage called the bird net, surrounded the tower lantern room during migration season.

Old photographs also reveal another item at the top of the tower. During the Spanish American War, a halyard for signal flags was attached to the main balcony. These flags were used to communicate with passing vessels.

The lighthouse tower was a technological marvel in its day. Its guiding beacon could be seen many miles out to sea, and today it remains as a piece of history that is becoming less and less known. Some facts about the tower are:

TOWER FACTS

First lit on November 1, 1887, the tower is still an active navigational aid, maintained by the Ponce de Leon Inlet Lighthouse Preservation Association. The tower’s location is:

Latitude, 29 degrees 04 minutes 50 seconds north

Longitude, 80 degrees 55 minutes 27 ½ seconds west

The tower’s exterior is a cone with an interior cylinder. The walls at the first level are 8 feet thick and at the top they are 2 feet thick.

Number of bricks used: 1.25 million

Height of tower from ground to lightning rod tip: 176 feet 6 ½ inches

Focal plane height above sea level: 164 feet 6 inches (At construction the focal plane height was given as 160 feet above mean low water).

Number of steps from ground level to lantern room: 213

Interior diameter of tower at first level: 12 feet

Diameter of foundation: 45 feet

Depth of foundation: 12 feet

Illuminant: third order rotating Fresnel lens constructed in Paris by Barbier, Benard & Turenne, c. 1901. This lens was first used in the tower from 1933-1970, following the removal of the original first order fixed Fresnel lens. The third order lens was restored and returned to service in the tower in 2004.

Characteristic: six half-second flashes, five of which are each followed by a two second eclipse. The final half-second flash is followed by a 17 second eclipse. This long eclipse is created by four panels of reflecting prisms, two of which form an access door into the lens’ interior. A single rotation of the lens takes approximately 30 seconds.

1887

1899

1922

1982

2007