There are few documented instances, and little written information about African-American lighthouse keepers in the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment or Service. In the nineteenth or very early twentieth centuries, African-Americans just did not have anywhere near the same employment possibilities as white keepers. In fact, it was not until after the Civil War and the post-Lincoln policies of the Reconstruction period that African-Americans were finally being offered governmental positions at all, never mind as “official” keepers and assistants at stations in the south or the nation, for that matter.

In those early days, and in some documented cases, while the official keeper was white, he often hired a black man, or before the Civil War, used his slave to actually do some or all of the work at the lightstation. In many of these transactions, if the situation were discovered, it would be ample cause to have the “official keeper” fired. But sadly, the whole business was frequently swept under the rug.

There are only a few instances where early African-Americans have been identified as keepers. The Chesapeake Chapter of the United States Lighthouse Society has published a list on their website with pictures of either the keepers if available, their lighthouse stations, and the service records of some of the African-American keepers who served in the Chesapeake Bay area.

A few of the most well-known of early African-American keepers identified are highlighted here. African-American, and most likely a slave, “Aaron Carter,” labored at the Cape Florida Lighthouse in the 1830’s. On July 23, 1836, the Seminoles attacked the station and Carter, and his owner, Assistant Keeper Thompson, were able to reach the safety of the tower and locked the door. As they scrambled up the steps, they hauled a powder keg with them. The Seminoles set fire to the tower and the flames burned up the wooden staircase. Both Thompson and Carter were in serious danger. Together they chopped the supports to the wooden steps below them to prevent the Seminoles from climbing higher, and the staircase crumbled to the base. Regrettably, it only provided more wood to the fire inside of the tower. Trapped at the top on the edge of the lantern platform, with bullets whizzing around them, Thompson decided that a quick death was better than being burned to a crisp. He threw the powder keg to the fire at base of the tower and the huge explosion added more fuel to the fire. We can only assume that Carter did not want a slow death, so he stood up. Bullets whined about him and Carter slumped to the platform, dead. Unfortunately, not much else is known about him. Thompson stayed in the tower overnight and it was noticed that the light was not lit that night. A day later Thompson was rescued. He recovered and returned to lighthouse service.

Cape Florida Lighthouse

In 1851, several naval officers who would eventually become members of the Lighthouse Board, which later reformed and “professionalized” the lighthouse service in the years following, were inspecting lights and floating lights or what are now known as lightships. Their efforts would become part of a report to Congress which served as the basis for standards for lighthouses and their keepers. While reviewing some early floating lightships in New York Harbor, then and now the largest and most important port in the nation, one vessel was boarded and they found no crew on board, “save for a young black boy aged 12 and the vessel in very bad condition.” At their recommendation, the boat was immediately taken off station, the “keeper” and crew arrested, and the “boat” towed off to be salvaged.

Unfortunately, it was not just a color line that limited African-Americans in those days. Politicians with connections to the political party in power certainly could and did arrange for political opponents to be fired and allies to get hired for Federal positions like lighthouse keepers.

Interestingly, things do change in Federal hiring practices a few years later. In the early 1880’s Congress established a Civil Service Commission specifically charged with the replacement of what was called the ‘spoils system.” To explain hiring at that time, one might say that “It was not what you know, it was who you know.” Many black families combatted that discrimination and prejudice by putting a high priority on education.

One example of such priority was the story of William Major Parker. Parker was a pioneer in his career as a keeper at on the Eastern Shore of Virginia at Assateague Lighthouse and later Killick Shoal Lighthouse. Parker enrolled at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in the Fall of 1873 , now Hampton University. Like many historic black colleges, Hampton was established in the Reconstruction Period to give blacks the skills they needed to own and operate farms or start business of their own. Parker impressed one of the white sponsors of Hampton, because he was appointed an assistant lighthouse keeper at Assateague Lighthouse and later he was promoted from assistant keeper to keeper at Killick. This appointment generated controversy. However, Parker garnered praise for his work and dedication, so much so, that when he was summoned to join a posse to assist in capturing a murdered, he concluded based on his obligation to keep the light active, that he would not participate. He was arrested and jailed. The Federal Department of Commerce, in charge of U.S. Lighthouses at the time called on the Federal Department of Justice to defend Parker. The charges were dropped. Parker’s case had national legal consequences. Parker worked for the US Lighthouse Establishment for thirty-five years, and died in service.

William Major Parker, Curtesy of the U.S.L.H.S

William Augustus Hodges served as the first African American lighthouse keeper at the Cape Henry Lighthouse in 1870. Cape Henry is also the First American Lighthouse. Called Old Cape Henry, because a taller new one was built next to it, Cape Henry was the first Public Works building built and lit by the United States Government in 1794. Hodges and his well-off family moved between Virginia and New York because of persecution, especially after the Nat Turner Rebellion. Hodges received a few months of schooling, and used the Bible to teach himself to read and write. He was a minister and a journalist and actually spied for the Union during the Civil War.

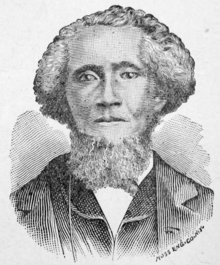

Willis Augustus Hodges

In 1870, Hodges was appointed night inspector for Old Point Comfort Lighthouse. This lighthouse experience paved his way to serve at Old Cape Henry in the head or principal peeper’s quarters in 1873. He was in charge of three assistant keepers.

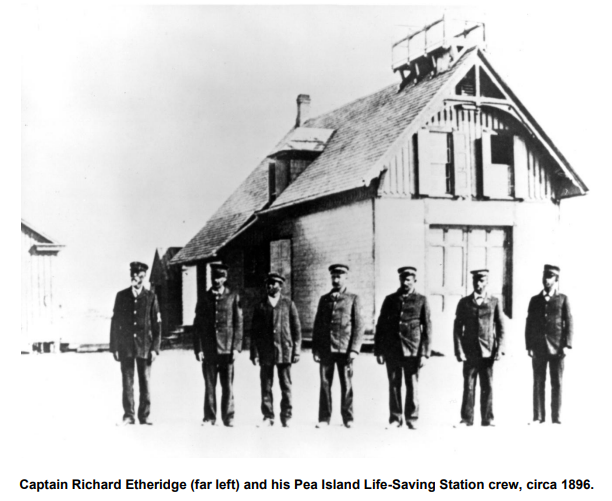

The first officially appointed African-American lighthouse keeper in the United States was Richard Etheridge who was assigned as head keeper at the Outer Banks Pea Island Life-Saving Station in North Carolina in 1871. Born into slavery, he became a prominent figure in American maritime history. Despite being a slave, he managed to get a formal education, and after the Civil War, Etheridge enlisted in the Union Navy North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, gaining an enormous amount of experience in maritime operations.

During his time as a lighthouse keeper at Pea Island, Etheridge and his crew was credited with saving many lives, despite challenging weather conditions, and dangerous currents. Etheridge also served as an advocate for maritime safety and equality. He actively recruited and trained young black men to become surfmen. To this day, the Richard Etheridge Scholarship Fund continues to provide financial assistance to African-Americans who are pursuing careers in the maritime industry. There are several books of note which recount the life of Etheridge and they include “Fire of the Beach: Recovering the Lost Story of Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island Lifesavers” by David Wright and “The Keeper’s Path: A Journey into the Life of Richard Etheridge of the Pea Island Life-Saving Station” by Courtney Anne Steward.